THE GLOBE AND MAIL, THURSDAY, APRIL 19, 1984

Her ears are

tuned to a

voice stilled

almost 40

year

BY KAY KRITZWISER

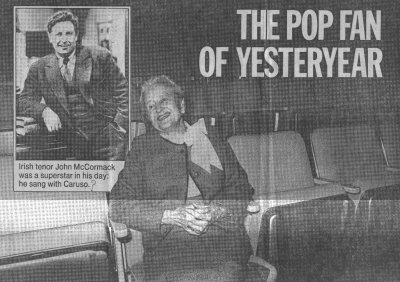

JOHN McCORMACK, the Irish tenor who was "born with a lark in his throat," has never stopped singing, at least not for the pilgrims who will arrive in Buffalo next Monday for a Centennial celebration of his birth.

Among the Toronto visitors will be Bertha H. White. In her Toronto apartment, she sits at a Victorian tea table, lights the candles in silver branches and pours tea into Crown Derby cups where the thin lemon slices float to perfection.

Not by the remotest stretch of fancy does Mrs. White, her silver hair piled high into place with a tortoiseshell comb, resemble today's pop music fanatics who squeal after a Michael Jackson or a Boy George. But when it comes to John McCormack, Mrs. White is an 85-year-old groupie.

Her eyes glow like the polish on her cherrywood table as she talks of the Irish tenor she never met. "Since 1971 when I began all my research, it has been the most rewarding thing I have ever done," she says.

John McCormick died almost 30 years ago, and Mrs. White is by no means the only fervent fan still devoted to his memory. Buffalo has proclaimed April 24 John McCormack Day. On that evening a Centennial concert will be given in Canisius High School auditorium, the very site where McCormack gave his farewell U.S. concert on March 16, 1937. The program will include Ireland-born tenor Niall Donoghue, who lives in Buffalo, Suzanne Thomas, a harpist, and Mildred Paella, pianist. There will also be a presentation of original McCormack recordings.

When she goes to Buffalo (accompanied by her daughters, Janet FitzGerald and Paula Pezzack) Mrs. White will be welcomed as one of the three honorary vice-presidents of the John McCormack Society of Ireland, an honor she received in 1981.

In 1982, she was invited to attend the opening of the restored foyer in the National Concert Hall in Dublin, dedicated to the tenor's memory. "The president of the society, 1iam Breen. invited me to the champagne party for 12 which he gave after the ceremony. Oh, it was lovely. And just the other week or so, I had a phone call from Mr. Breen to make sure I was coming to Dublin for the June celebrations. And of. course I am... Where John McCormack is concerned, I'm more Irish than the Irish."

The Dublin celebrations will include five McCormack concerts "but I don't think I'll go to all of them." She has friends to visit: among the most cherished are Cyril Count McCormack and his sister Gwen McCormack-Pyke, children of the singer. "Cyril inherited the Papal Count title from his father. Cardinal Hayes made John a Papal Count in 1928 and it was a hereditary title. Cyril lives in the Wicklow Hills near Dublin. He is 76 and his sister is 75 they're warm friends of mine."

In her lovely little sitting room, Bertha White explains her passion for a lilting Irish voice that was stilled on Sept. 16, 1945. "I had visited so many countries - to Russia 10 times, to Poland, Morocco, Spain, but I'd never got around to Ireland until September, 1970. All that winter I couldn't forget my visit. It was seeing all those places John McCormack had sung about on his records I'd grown up with, I suppose. I wanted to learn more about him so I went to our music library and I found so little reference to him and his work. That settled it. I was hooked." She has been to Ireland half a dozen times since, like a pilgrim to a shrine.

She has recorded almost two hours of research in two scripts interspersed with McCormack's recorded voice. She has played them a number of times to her book Her ears are tuned to a voice stilled almost 40 years ago club and church groups, but she brushes that away as unimportant. It's not herself, but the perpetuation of a legend that compels her.

She inserts a cassette into her recorder. ("Of course, I made these cassettes myself.") Thin but tender tones from a weathered record fill the room. When Irish Eyes Are Smilin', the voice sings, and memories of the scratchy Victor records of childhood flood the room. ("In the lilt of Irish laughter, You can hear the angels sing," and the actuality of the sorrier side of today's Ireland falls away.)

Her first memories of The Voice go back to her childhood. (She came to Canada from England wheh she was 7.) On a cold sunny Saturday in 1913, she was sent to the Danforth Fruit Shop for lemons. Like a born storyteller, she relishes the tale: "I could hear the crunch of snow as I walked but as I neared Danforth, there was another sound coming over that frosty air - John McCormack singing Where The River Shannon Flows. It was being ground out on a grind organ, complete with a monkey in a red jacket and a golden-tasselled black cap. I can close my eyes and see myself standing there with my hands in my pockets, listening to that beautiful voice. I can still hear the rattle of my big cent as I dropped it into the tin cup the monkey passed around."

Not long after, her father bought a tall mahogany gramophone and a collection of Irish ballads sung by McCormack. Now a room in her apartment holds more than 500 recordings, long-plays, 78s, tapes -"1 never pass a record shop." On one shelf stand six biographies on McCormack, each autographed for her by his son Cyril.

She has started on her fifth big scrapbook of clippings, programs and photographs. She haunts the Old Favorite Book Shop. She is a fan of Clyde Gilmour, the Toronto music historian - "he's a staunch McCormack advocate." When she picks up a first printing of the book Lily Foley McCormack wrote about her famous husband, out falls a shamrock-sprigged bookmark: "May you be in heaven an hour before the devil knows you're dead."

One wall is covered with, memorabilia. One item is a large framed photo of John McCormack when he appeared in his first Hollywood movie, Song 0' My Heart, which he shared with actress Maureen O'Sullivan. For that film, he got $500,000. It paid for the first home he built in Beverly Hills. Though he was born of very poor parents in Athlone, the fourth of 11 children, he became a wealthy performer even by today's superstar standards. One of the clippings in her collection reports that when, McCormack sang in the New York Hippodrome on April 18, 1918, 7,000 people listened to him and the receipts were about $34,000. When he sang a few months later for the Fighting Sixty-Ninth battalion, his receipts were $35,000.

"He loved good food and beautiful surroundings and he had a beautiful art collection. He had a Frans Hals nd Rodin's bronze statute of Romeo and Juliet., Cyril told me bout some of his painting. - he had a Rembrandt, a Gainsborough, a Corot and a Whistler. I had my picture taken beside the portrait Sir William Orpen painted of Mr. McCormack."

Once the singer's struggling days were over, he indulged his love of cars. He owned 12 Rolls-Royces. Yet he remained humble: before every performance he would find a Catholic church and pray. "He said it was 'saying grace for music.'"

Mrs. White has evolved her own way of saying grace for-the McCormack legacy. A plaque concealed behind her sitting room door is titled "Great Music for Everyone: Be it known that Mrs. F. Melville White has endowed seat R6 in Roy Thomson Hall in perpetuity. To the Irish tenor John McCormack, the Meistersinger 1884-1945."

"I've sat in it just twice," she says.

Mrs. White is still adding to her collection of the tenor's concert programs. She has the program for his first concert in Toronto, when he sang from his wide operatic repertoire, in Massey Hall on April 17, 1913. And she has a copy of his final Toronto program given in Massey Hall on Oct. 30, 1931, when he sang Irish folksongs like Smilin' Kitty O'Day and Garden Where The Praties Grow, and ballads like Rose Of Tralee and Believe Me If All' Those Endearing Young Charms. "But we tend to forget that he had an operatic repertoire of 23 operas," Mrs. White said. "Why, Dame Nellie Melba invited him to sing with her in Covent Garden when he was just 23. But she would never let him take a bow with her. She told him Melba bowed alone." The tone of Mrs. White's voice demolished Melba. "He sang with Tetrazzini for many seasons and. she loved him. He was a favorite singer of Queen Alexandra, too, and' of Queen Mary." One of the souvenirs to which Mrs. White is most attached is a Savoy Hotel dinner menu on which the Italian tenor Enrico Caruso drew an impish caricature of McCormack and himself. He sketched both likenesses and enclosed them in the outline of a wine' glass. The date is thought to be 1914; during the Covent Garden seasow when both tenors sang.

A bonus of her continuing research is the number of new friends made, often in unlikely places. "When I go to Buffalo with my daughters for the concert, my friend Margaret O'Reilley is coming with us. I met her - we call her Mave - unexpectedly one morning on the subway. When I sat down I noticed I was still carrying a letter addressed to the secretary of the John McCormack Society of Ireland. I said out loud, 'Oh bother, I. meant to post this.' The woman sitting beside me glanced at the envelope and said, 'Why, that's my uncle.' That's how our friendship, began."

In Buffalo she will visit Carole I Brown Knuth and Dr. Leo Knuth, co-authors of The Tenor and The Vehicle: A study Of The John McCormack/James Joyce Connection. "They spent a whole afternoon: with me here, looking at my collection. They persuaded me that all my material must go into archives somewhere. So I have arranged to give it to the music department of the Metropolitan Toronto Library."

When the collection goes into the archives, there may not be a plaque for Mrs. White. She quotes Sigmund Freud to emphasize of how little importance recognition is for herself. "Freud reminded us that 'Immortality is being loved by many anonymous people.' I'm just one of McCormack's many anonymous people."

Many thanks to Bernie Power for making this 1984 newspaper article available. Sadly this grand old lady has since passed on.